Few words before we start…If you’ve just joined in the “Choosing fabric for machine embroidery” theme, we’d like to remind that the piece is the third in the row. And, as the first two articles “pave the way” to understanding the present one, it’d be more helpful for you if you read them before moving onto the third one.

The first (introductory) article is available here. It describes the general guideline which every embroiderer should follow when choosing fabrics for various embroidery projects.

The second article is available here and it shows how to apply those machine embroidery rules when working with woven and knitted fabrics.

Introduction

Today’s article deals the role of fabric properties in assembling embroidery projects. Again, like in all our previous articles on the theme, we won’t bore you with technical terms and overly detailed descriptions. It’d be too tedious and time-consuming.

It should also be noted, that the list of fabric properties, presented in the piece won’t be an all-inclusive one. Properties like thermal resistance, flame resistant moisture transmission, wicking, water proof and some other have little interest for machine embroidery. Thus, we won’t dwell upon them. Agreed? Well, then, let’s begin!

Fabric properties are characteristics of fabrics, which determine the way fabrics “behave” during stretching, washing, ironing, sewing etc. Fabric properties, which are important for machine embroidery, include the following ones:

1 – Drape,

2 – Stretch,

3 – Surface characteristics (textured, flat, sleek, matte etc.),

4 – Yarn severance (how threads of fabric react to needles),

5 – Seam slippage (happens when yarns or even filaments pull away from each other because of some pressure: embroidery stitches, hoop pressure etc.

6 – Wrinkle factor.

7 – Shrinkage,

8 – Fray factor,

So, the list of properties, valuable for choosing fabrics for machine embroidery is given. Now let’s elaborate on each of the lot in a more detailed way.

Fabric drape

Fabric drape is basically an ability of a fabric to take up and keep certain shape. There’re three degrees of fabric drape:

1- Light (fluid) drape. Fabrics of light drape don’t hold their weight at all. In a garment such fabrics tend to flow down the body, like they’re liquid. When choosing fluid fabrics for machine embroidery it’s very important to find the type of stabilizers and a design, which won’t change the drape. Examples of such fabrics Burnout Jersey knits, light fleeces, silk and polyester satins, Crepe de Chine etc.

2 – Medium (moderate) drape. Fabrics of moderate drape are easier to use in embroidery projects. They are compatible with a wider variety of designs and stabilizers. Examples of such fabrics will be cotton jersey knits, velvet, lawn etc.

3 – Heavy (full-bodied) drape. Fabrics of heavy drape hold their weight very well. Usually they are quite crisp and stiff. Examples of such fabrics are taffeta, tweed, gabardine, Bedford Cord, Duchess etc.

When choosing fabric for machine embroidery according to its drape, you’ll operate (describe what you want in the fabric store) with these exactly terms.

So, why do you need to know what drape does a certain fabric have? Well, because drape of the fabric determines the choice of stabilizers and designs. Fabrics of light (fluid) drapes won’t work for dense fill-stitch designs as such designs will simply change the fabrics draping quality. Same rule applies to the choice of stabilizers. Fluid fabrics (and items, made of them) usually can’t be stabilized with heavy backings or toppings. Usually wash-away, heat-away and tear-away stabilizers are used with fluid fabrics. If, for some reason, support, provided by the abovementioned stabilizers isn’t enough, mesh-like semitransparent cut-away backings are used. Fabrics with moderate drape are more forgiving on that matter. They can accommodate a wider variety of designs and stabilizers. Fabrics of full-bodied drape have no restrictions on this wise.

What’s more is that fabric drape may influence positioning of designs on an item. Further we’ll give an example of how exactly fabric drape affect machine embroidery process.

Example: Machine embroidery of a Burnout jersey knit T-shirt.

Design choice: Burnout jersey knit is very lightweight fabric of it light (fluid) drape. This means that, when choosing such fabric for machine embroidery, we will definitely use light stitch designs.

Tattoo Vintage Style Machine Embroidery Design, for once, is a good choice for such lightweight fabric. Machine embroidery design Angry Tiger Face, on the other hand, will definitely change the drape of the T-shirt.

Design placement: Our lightweight jersey knit drapes very well. This means that when the T-shirt is being worn, some of its areas will have quite a close fit to the body. So, in order for it to keep its drape, designs should be embroidered in areas, which are not affected by stretch (e.g. back or lower front). Chest area, as it stretches the, might pose some issues both in choosing designs and their positioning. The designs shouldn’t affect draping quality of the fabric. They should be neither too big, nor too dense. Otherwise, when the T-shirt will be worn either the embroidery stitches or the fabric will get distorted.

Stabilizer choice: As Burnout jersey knit is not only fluid but also elastic, we’ll need a stable backing paired with temporary spray adhesive. As, “Burnout” in these types of jersey knits means “transparent”, we’ll have to adjust our choice of stabilizers to “invisible” ones. There’re several stabilizers which can be called “invisible”. All water-soluble, heat-away and tear-away ones can be removed from the fabric completely, so they’re practically “invisible”. Another type of stabilizers applicable to the fabric in question is a semi-transparent light cut-away backing (like Gunold Soft n’ Sheer or similar). These types of stabilizers can support designs of light to medium density. All of them will suite our purpose, as long as they either have an adhesive layer (e.g. Filmoplast by Gunold, Filmoplast by H54 Vlieseline, Sulky Sticky by Sulky, Starlite sticky by Starlite, etc.) or can be used with temporary spray adhesives (not films).

Fabric stretch (elasticity)

Fabric stretch will determine the choice of stabilizers, hooping methods, designs and needles. Really elastic (stretchy) fabrics, be it woven, knitted or non-woven ones, are treated like knitted textiles. We already know that machine embroidery of elastic fabrics requires ball-point needles and quite stable backings (preferable with an adhesive layer). Designs for machine embroidery of such fabrics should “agree” with the level of elasticity of each particular fabric.

Example: Designs for machine embroidery of rib knit sweaters should never have large elements. Otherwise, when the item is worn, its fabric won’t be able to stretch under the stitches of the embroidery.

More detailed information on machine embroidery on stretchy fabrics is available in the second article of “Choosing fabric for machine embroidery” series, in the section with the knitted fabrics.

Surface characteristics

Textured, flat, sleek, matte, etc. – all these characteristics of fabric surface were more or less discussed in the second article of “Choosing fabric for machine embroidery” series. Thus, instead of getting into the details again, we’ll just give you the most important highlights.

So, woven and knitted fabrics all have different surface characteristics, which mostly depend on the yarn and the type of the weave. The most agreeable (easy to embroider on) fabrics are of plane or twill weave with thin yarns of blended (polyester with some natural fiber) content. Such fabrics have flat, matte surface which can endure needle punctures, dense stitching, hoop pressure. So, in general, in order for a fabric to be machine-embroidered well, it should somehow achieve “flat and matte” surface structure. How can an embroiderer do it? With the help of stabilizers, of course. Hooping method and choice of designs, threads and needles can’t change the fabric, so they’re adapted to its demands.

Silk Satin

Example: Satin weaves made of thin yarns (Duchess, Silk Satin) usually have very sleek and slippery surface. Difficulties such fabrics pose for machine embroidery include:

~ Hooping issues. As, these fabrics are delicate and slippery, they might shift during the hooping. In order to avoid fabric shifting, embroiderers wrap both the inner and the outer hoop with thin, matte fabric. Such measure also prevents the fabric yarns from being pulled away from each other under the pressure of the hoops.

~ Stabilizer choice. Duchess and other delicate Satins are embroidered on self-adhesive tear-away or cut-away backings. You can also use temporary spray adhesive with non-adhesive stabilizers.

~ Design choice will largely depend on the cut of the embroidered-to-be item and its draping demands. Usually too dense designs, on that matter, are left aside.

~ Needles and threads for sleek, lightweight satins are always thin (needles are also sharp).

~ Same approach is applied to fabrics of textured surfaces. They should be “made” to be flat and matte.

Example: Terry cloth towels and bathrobes are all embroidered with topping and backing. Faux fur trimming of a Christmas stocking is just the same. Obviously, the hooping method, the needle choice and design settings are all adjusted accordingly.

Yarn severance

Yarn severance is reaction of fabrics yarns to needle cutting. This fabric property will determine the choice of, yes, you guessed it, needles. What matters in choosing embroidery needle is the size and type of its tip (point). When the point type is chosen correctly, the needle won’t cut through fabric yarns and the fabric will be damaged. Yarns o knitted fabrics will unravel and run. Woven fabrics, on the other hand, develop either holes or, less frequently, their threads might run too. Non-woven fabrics will develop holes only.

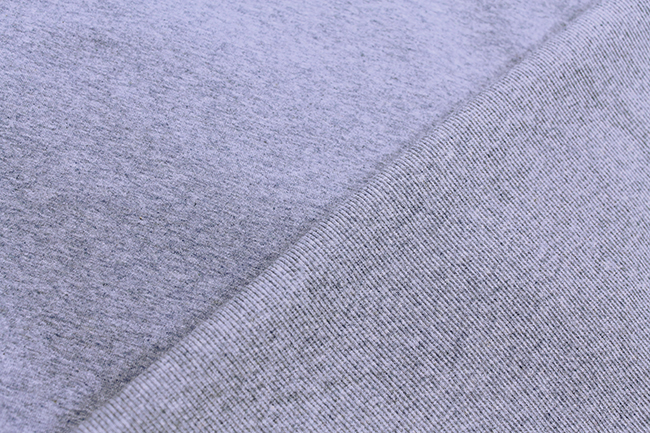

Knitted fabric

Example: Knitted fabrics should generally be embroidered with ball-point needles. Lightweight satin-weave fabrics should be embroidered with thin, sharp point needles.

Each fabric has its own preferences on the embroidery needle choice. More detailed information on embroidery needles is available in here.

Seam slippage

Seam slippage is a term, borrowed from sewing. This term denotes a type of fabric damage, when stitches of seams cause threads (yarns) of the fabric to pull away from each other. Such a sad thing may occur when the chosen embroidery threads are too thick for the weave of the fabric.

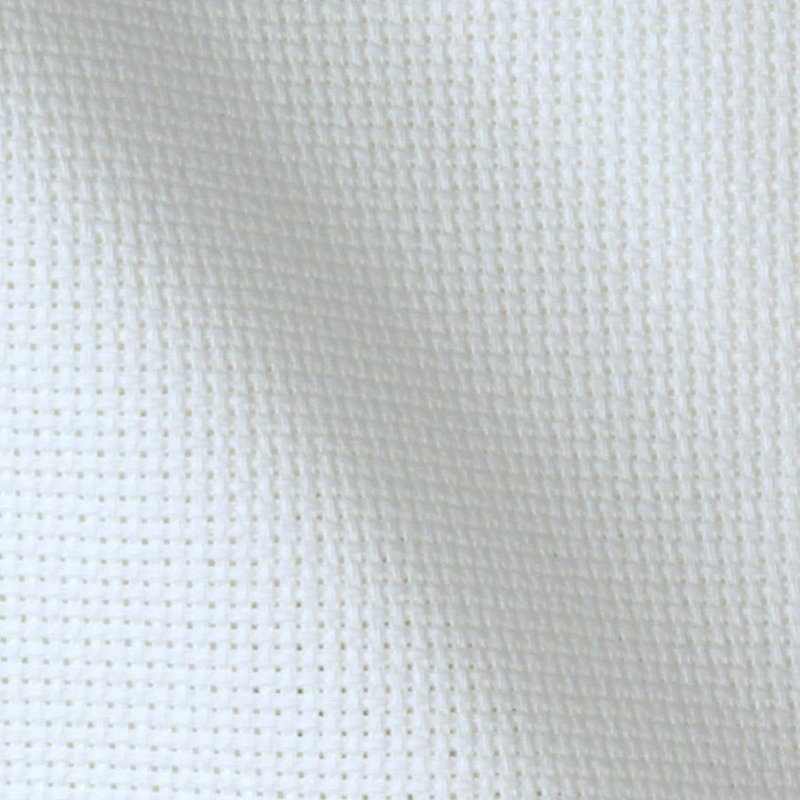

Example: Machine embroidery of cross-stitch designs on Aida fabrics. If you choose threads that are too thick for the dimensions of Aida fabric weave, embroidery stitches will literally make tiny weave openings look like giant holes. As a result the project will be ruined.

Besides the thick threads, the cause of seam slippage (or yarn pull away) could be the arrangement of stitches in the design. The most frequent “culprit” is too dense stitching.

Example: Think of any design of the letter “O” done in dense satin stitching. The inside of the “O” will get significantly larger amount of needle puncturing then the outer outline. This means that threads will be “packed” in a much denser manner on the inner side of the letter, than on the outer side. If a fabric has relatively loose weave structure (like with light knits, Burlap, Lawn etc.), the inside part of the “O” will simply be damaged.

With non-woven fabrics there’s no seam slippage, as there such fabrics don’t have any weave-patterns. Instead, such fabrics simply develop holes.

Example: Try embroidering the same “O” design on leather. The dense satin stitching will break the leather.

How to avoid mishaps of the kind? Here’re some tips on the matter:

~ Choose the designs (or adjust the density) according to the demands of the fabric.

~ Choose the size of the threads according to the demands of the fabric and the to-be-sewn designs.

~ Try using a light to medium weight topping when embroidering demanding fabrics.

The rest of the properties (fray factor, shrinkage, wrinkle factor) are connected to the fiber content of fabrics. So, when choosing fabrics for machine embroidery, you’ll also have to check their fiber content.

What an embroiderer should know about fabrics fiber content? Well, first of all there’re three main types of fabrics according to their fiber content:

~ Natural (with cotton, silk, wool, linen, jute fibers – anything coming from Mother Nature herself),

~ Man-made (rayon, viscose, cellulose, metallic fibers etc.)

Spandex

~ Synthetic (polyester, nylon, acrylic, polypropylene, Lastex (used for Spandex), ect.)

The most durable and “work-able” fabrics are blends of the three types of fibers. If it’s a pure type of fabric, it always has limitations either during embroidery or further in use. So, now that the highlights are given, let’s continue with the fabric properties, important for machine embroidery.

Shrinkage

Shrinkage factor is really important when choosing fabric for machine embroidery. There’re basically two main reasons for shrinkage:

1 – Fiber content. Fabrics that shrink the most are those, made of natural fibers. Synthetic fabrics shrink less of all.

2 – Type of weave. Knits and loosely woven fabrics tend to shrink more than other types of fabrics.

Why should embroiderers take shrinkage of fabric into account when assembling their next embroidery projects? Well, because shrinking changes geometry of the fabric. And, as chances are, all the variables of the project (stabilizer choice, design settings, etc.) are assembled according to the existing geometry of the fabric (its thickness, length etc.) So, with the change, caused by the shrinkage, all the chosen variables will not suite the job any more. Bottom line, shrinkage factor changes the process of machine embroidery, adding to it an extra step of pre-shrinking.

Waffle weave towel

Example 2: Machine embroidery of a Waffle weave towel. Being notoriously unstable as a weave type, waffle weave fabric shrinks a lot. Let’s say that you’ve embroidered it without pre-shrinking it first. After the first wash, when the fabric reduces in size, the embroidery will get distorted.

As a rule, shrinkage matters if you’re choosing fabric for machine embroidery and not a ready-made blank or piece of garment. It happens so, because manufacturers, before sewing the garments or blank, pre-shrink the fabrics. Thus, though still present, shrinkage factor of ready-made clothes is less prominent than that of “raw” fabrics.

Tip: If your line of work include sewing and only then decorating the pieces with machine embroidery, shrinkage factor of various fabrics is all the more important. So, to make your life easier, before starting a new project, consult with one of the numerous online “fabric shrinkage calculators”.

Fray factor

Fabric fray factor is of concern for such projects as machine embroidery of appliqué designs, patches etc. When choosing fabric for machine embroidery of these types, you only want to work with fabrics that don’t fray or fray little. The only fabrics that don’t fray at all are non-woven fabrics (we’ll speak about them in detail in the fourth article of the series). The rest of the textile kingdom does fray. Woven fabrics generally fray less because their weave is much more stable than those of knitted fabrics. Plain Weave fabrics, on this matter, fray less than other types of weave.

Besides the weave, fiber content of the fabric can also have its effect on fray property of fabrics.

Example: Viscose and Synthetic organza. Synthetic fibers undergo “special” treatment, which makes them a bit more rigid and less pliable than viscose ones. Thus, when synthetic fibers are interwoven into threads, which in their turn are interwoven in a certain pattern (plain weave), they are “forcibly” bent. That is why synthetic organza has this crisp, “starched-like” feel. So, when the fabric is cut, its fibers become unbent and if the edge isn’t treated (by a seam or a fray-check liquid) it starts to fray. So, when organza is used in appliqués or even FSL projects , it’s helpful to know its fiber content.

Wrinkle factor

Reaction to wrinkling is not an obvious and most decisive factor when such question as choosing fabric for machine embroidery comes up. However, there’re embroidery projects, where this factor should be taken into account.

Example: Machine embroidery with textured threads (acrylic, wool threads etc.) The whole point of using such threads is enhancing the texture of embroidery patterns. With acrylic threads one can create embroidery with almost “fur-like” fuzzy textures. Such an effect looks well on designs of animals, certain flowers (like mimosas) etc. If you’re working on projects of such kind, wrinkle factor is important for choosing fabric for machine embroidery. How so? Let us explain.

The thing is, if a fabric wrinkles easily, it has to be ironed a lot. Acrylic and wool threads, when ironed, lose their texture and won’t fuzz any more. Thus, to be able to enjoy the effect of such threads, opt for fabrics that don’t wrinkle.

The list of textile properties which one should take into account when choosing fabric for machine embroidery is through. Now that we’ve covered this part of our journey in the realm of fabrics and machine embroidery, woven and knitted fabrics can be rightfully called not just your acquaintances but your close friends. And, hopefully all embroidery projects featuring all those fabrics will come out just as you wish! What? What about non-woven fabrics, you ask? Don’t worry, we didn’t forget about them! How could we? All those leather jackets and bags, waiting to be embroidered, right? We’ll speak about non-woven fabrics in the next, fourth and final installment to the series. For now, though, we call it a day. Happy sewing to everyone and see you all in the next article.

You may also like

Woven and knit fabrics explained

Author: Ludmila Konovalova

My name is Ludmila Konovalova, and I lead Royal Present Embroidery. Embroidery for me is more than a profession; it is a legacy of my Ukrainian and Bulgarian heritage, where every woman in my family was a virtuoso in cross-stitch and smooth stitching. This art, passed down through generations, is part of my soul and a symbol of national pride.

Date: 18.05.2024

Get Sign-In Link

Get Sign-In Link Login with Google

Login with Google Login with Facebook

Login with Facebook Login with Amazon

Login with Amazon Login with Paypal

Login with Paypal